The Making of an Author: David Sherman’s Literary Journey

David Sherman’s literary journey commenced during his time in the service, where he discovered his passion for storytelling. After leaving the military, Sherman embarked on his writing career, drawing extensively from his experiences. His approach to writing is methodical and informed by his academic background in science from a prestigious university, where he once studied biochemistry, further enriching his narrative capabilities. His first book, Knives in the Night, marked the beginning of a prolific career that spans several acclaimed series, including the renowned Starfist series, co-authored with Dan Cragg.

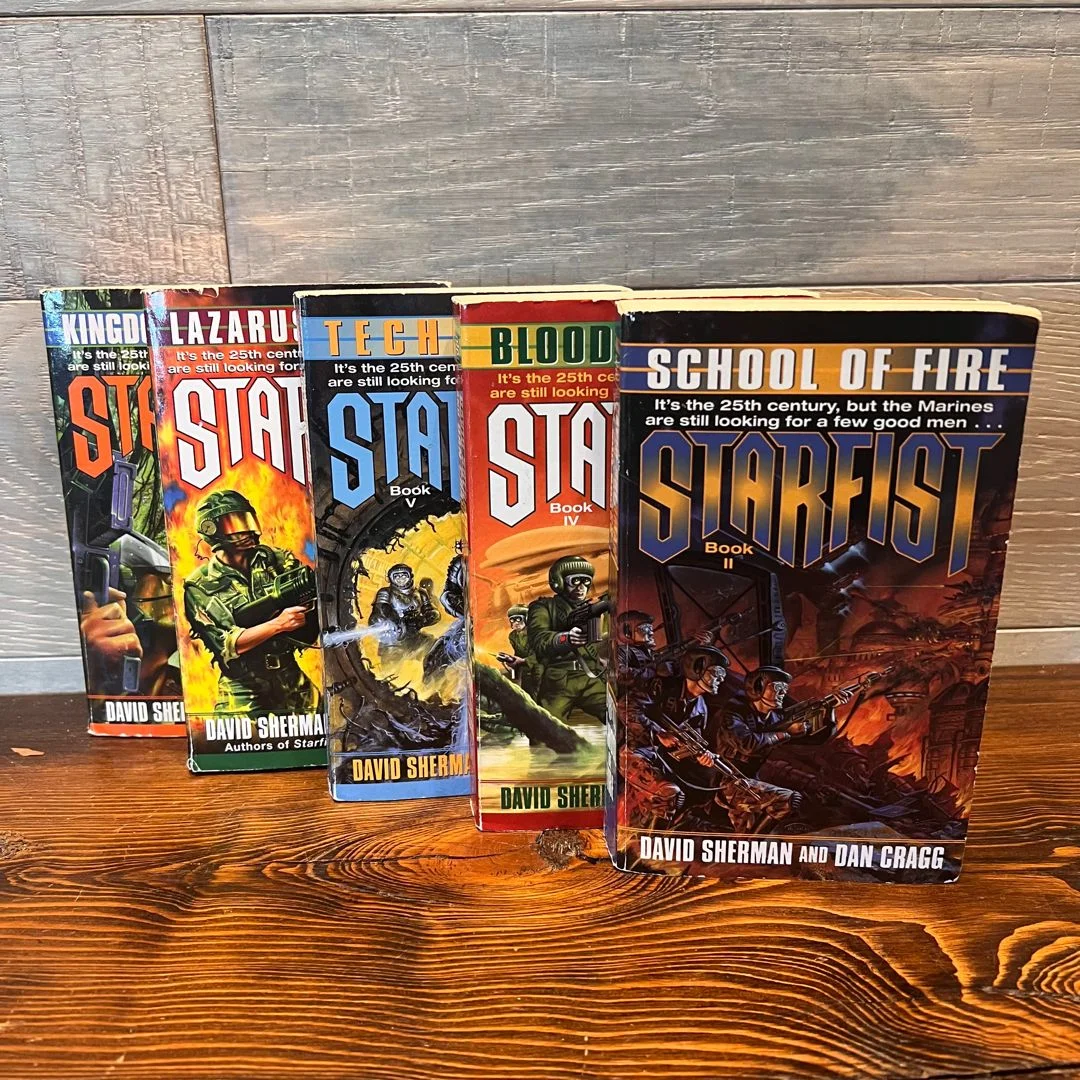

Starfist Series: A Deep Dive into Military Science Fiction

The Starfist series is perhaps David Sherman’s most significant contribution to the military science fiction genre. With its inception, Sherman and his co-author created a compelling universe that mirrors the complexities of war, infused with speculative technology and interstellar conflicts. This series not only showcases Sherman’s deep understanding of military tactics but also his ability to intertwine these elements with dynamic character development and a richly crafted narrative.

Recurring Themes and Characters in Sherman David’s Works

In Sherman’s works, themes of duty, honor, and the moral complexities of warfare are recurrent. His characters, often depicted as stoic yet deeply introspective individuals, reflect his own military background and his broader reflections on the nature of service and sacrifice. These themes are woven seamlessly into his narratives, providing a resonant and engaging reading experience that explores the depths of human resilience and the impact of war.

Fan Favorites: Highlighting the Best of Starfist Books

Among the Starfist series, books like First to Fight stand out not only for their thrilling plots but also for their deep dive into the psyche of soldiers. Fans and critics alike have lauded Sherman for his authentic depiction of military life and for providing a voice to the often-unsung heroes of the armed forces. His books have received numerous awards, affirming his role as a significant figure in science fiction and military literature.

David Sherman’s Approach to World-Building and Character Development

David Sherman’s meticulous world-building is evident in his detailed descriptions of intergalactic warfare and the inner workings of a military unit far from the familiar terrains of Earth. His background in microbiology and biochemistry adds a layer of scientific authenticity to his work, enriching his characters’ interactions with their environments and the technologies they use. Sherman’s commitment to character development is particularly noted in how he portrays the evolution of his characters over time, influenced by their experiences and the landscapes they inhabit.

The Impact of the Starfist Series on the Sci-Fi Genre

Sherman David’s Starfist series has profoundly impacted the sci-fi genre, particularly in how it blends authentic military detail with speculative fiction. The series has set a benchmark for narrative depth and complexity, pushing the boundaries of the genre and influencing a generation of writers and fans. Through his imaginative and insightful storytelling, Sherman has expanded the possibilities of military science fiction to explore fundamental questions about humanity and the future of warfare.

What’s Next for David Sherman: Upcoming Projects and Releases

Looking ahead, David Sherman continues to explore new frontiers in both his personal and professional life. His upcoming projects are eagerly anticipated by fans around the world, promising more of the rich storytelling that has defined his career. As he joins new organizations and collaborates on international literary projects, Sherman remains a prominent figure in science fiction, continually pushing the envelope on what is possible in military narrative fiction.

David Sherman’s contributions to literature span a remarkable breadth of themes and narratives, each infused with his unique voice and profound understanding of human and martial conflicts. His novels not only entertain but also challenge and provoke thought, offering insights that resonate with readers long after the last page is turned. As he moves forward with new works, his continued influence on the literary and science fiction landscapes is assured, bolstered by his past achievements and ongoing innovations in storytelling.